Startup valuation stands as a critical, yet often perplexing, hurdle for founders and investors alike. Establishing a company’s worth is fundamental not only for securing investment but also for vital strategic activities such as creating employee stock option plans (e.g. a 409A valuation in the US), planning exit strategies, and informing overall business planning. However, particularly for early-stage ventures, valuation presents unique challenges. These companies typically lack substantial operating history, possess limited tangible assets, and their future prospects are shrouded in significant uncertainty. This environment makes traditional valuation techniques difficult to apply directly.

Valuation as a Process, Not Just a Number

A common misconception is that startup valuation aims to pinpoint a single, definitive “right” number representing the company’s price. However, a more constructive perspective views valuation as a process and a tool for communication. The ultimate goal is not merely to set a price but to facilitate a transparent and productive negotiation between founders and investors. This process should help both parties develop a shared understanding of the company’s future potential and, crucially, the underlying assumptions driving that potential.

A valuation report serves as an input into the negotiation, laying out the key drivers of value and the assumptions behind the calculations. This approach encourages dialogue focused on the business fundamentals – the team, the market opportunity, the product, the financial projections – rather than anchoring the conversation to arbitrary figures potentially derived from selectively chosen, and often inappropriate, market comparisons. The emphasis shifts from haggling over a number to achieving alignment on the business’s trajectory and the risks involved. This framing manages expectations and underscores the collaborative nature required for successful fundraising.

Focusing on Potential over Performance

The Startup Distinction

Valuing an early-stage startup differs fundamentally from valuing an established company. Mature businesses often have years of financial statements, predictable revenue streams, and substantial tangible assets, providing a solid anchor for valuation. Startups, conversely, operate in a realm of high uncertainty. Their value proposition is typically rooted not in past performance but in future potential. Key value drivers include intangible assets like intellectual property, the strength and experience of the founding team, the perceived size of the market opportunity, network effects, brand recognition, and, critically, the projected ability to generate significant cash flows in the future. Methods relying heavily on historical data or the current balance sheet, such as Book Value or Cost to Duplicate approaches, often fail to capture this forward-looking, intangible-driven value. Startup valuation must therefore focus on assessing the likelihood and magnitude of future success, rather than solely reflecting current assets or earnings.

This focus on the future introduces significant challenges. Projections for revenue, market share, and profitability are inherently speculative for young companies, often representing ambitious targets rather than reliable forecasts. High failure rates are a stark reality in the startup world, adding another layer of risk that must be accounted for. Information asymmetry is also common; founders possess deep insights into their operations and vision, while investors must assess the opportunity based on limited data and their own market expertise. Furthermore, any quantitative valuation method, particularly the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) approach, is highly sensitive to the underlying assumptions about growth rates, discount rates, and terminal values. These factors underscore the difficulty in arriving at an objective valuation and highlight the importance of methodologies that can accommodate uncertainty and qualitative judgments. The inherent ambiguity necessitates valuation approaches capable of systematically integrating qualitative assessments of factors like team quality and market dynamics alongside quantitative financial forecasts. This inherent need for diverse perspectives logically supports the use of blended or multi-method valuation frameworks.

Common Valuation Methods: Separating Signal from Noise

The landscape of startup valuation includes numerous methodologies, some more applicable than others. While around ten methods are commonly referenced, practical application, especially for high-growth, early-stage companies, often narrows the field considerably. Understanding why certain widely known methods are often unsuitable for startups is crucial before exploring more appropriate techniques.

Critiquing Unsuitable Methods for High-Growth Startups

Several traditional or overly simplistic methods fail to adequately capture the unique characteristics of technology startups.

- Book Value: This method calculates value based on tangible assets minus liabilities as recorded on the balance sheet (Assets – Liabilities). For startups, particularly in technology and software sectors, the primary assets are often intangible – intellectual property, skilled teams, user bases, brand equity, and growth potential. The book value typically represents only a fraction of the perceived worth and fails entirely to account for future prospects. It is generally considered relevant only in distressed situations or liquidations, where the focus is on the minimum recoverable value from tangible assets. External analysis consistently confirms the inadequacy of book value for businesses driven by intangible assets and future growth expectations.

- Cost to Duplicate: This approach estimates value based on the cost required to replicate the business from scratch – building the product, acquiring similar assets, and hiring the team. While seemingly logical for some traditional businesses like a local service provider (e.g., butcher, barber) where assets are tangible and customer acquisition straightforward, it breaks down for technology startups. It fails to account for crucial intangible elements like proprietary algorithms, accumulated data, established user networks, brand reputation, strategic partnerships, and first-mover advantages, which are often expensive, time-consuming, or impossible to replicate directly. The sustainable competitive advantages typical of successful startups render this method largely unsuitable. External commentary frequently emphasizes the role of these hard-to-replicate intangibles and network effects in driving tech company value.

- Comparable Transactions (as a Primary Method): This method, often referred to as “comps,” involves applying valuation multiples (e.g., revenue multiple, ARR multiple, EBITDA multiple) derived from recent acquisitions or funding rounds of supposedly similar companies. While appealing due to its market-based simplicity, using this as the primary valuation driver for startups is fraught with peril. It can be crude, failing to account for nuanced differences between companies; it is pro-cyclical, reflecting market highs and lows rather than fundamental value; it is easily exploitable, potentially incentivizing misleading accounting practices to inflate the metric used for the multiple; and it provides a one-dimensional view, ignoring critical aspects like team quality, technology differentiation, or long-term strategy. Finding truly comparable private companies and accessing reliable transaction data is also notoriously difficult. Historically, this approach served more as a secondary check or sanity test after a primary valuation was established using other methods. While multiples have become popular, their simplistic application can generate biased results if not carefully contextualized, for instance, by applying them to projected future metrics rather than volatile current ones. The desire for straightforward, market-based benchmarks often clashes with the reality that each startup possesses unique risks and potential, demanding more than just an average market multiple. Relying solely on comparables ignores the company-specific deep dive necessary for a credible valuation.

- First Chicago Method: This method attempts to address uncertainty by combining elements of DCF and multiples to model different potential outcomes for the company, typically a best-case, worst-case, and a middle or base-case scenario. While potentially useful as a thought exercise, generating these distinct scenarios can be arbitrary and often lacks practical insight. When faced with the high degree of uncertainty inherent in startups, investing effort in developing multiple, potentially speculative, scenarios can distract from the core task. A more productive approach involves focusing the negotiation and analysis on what both founders and investors believe is the single, most rational outcome for the business. By concentrating on this central scenario, both parties are forced to rigorously examine and debate the underlying assumptions, risks, and opportunities within that specific pathway, fostering a deeper understanding and facilitating consensus on a rational basis for valuation.

Summary of Unsuitable Methods

| Method Name | Brief Description | Problem |

|---|---|---|

| Book Value | Net Asset Value (Assets – Liabilities) | Ignores intangible assets (IP, team, brand) and future growth potential. |

| Cost to Duplicate | Cost to rebuild the business from scratch | Fails to value intangibles (data, users, brand, network effects), competitive advantages. |

| Comparable Transactions (Primary) | Apply market multiples (e.g., Revenue x Multiple) | Crude, pro-cyclical, exploitable, one-dimensional; ignores company specifics; data scarcity. |

| First Chicago Method | Combines DCF/Multiples for multiple (best/worst/base) scenarios | Scenario generation can be arbitrary and lack insight; distracts from focusing on the most probable outcome. |

This critique underscores the need for valuation approaches specifically designed or adapted for the unique context of early-stage, high-growth ventures.

Practical Valuation Approaches for Startups: The Methods That Work

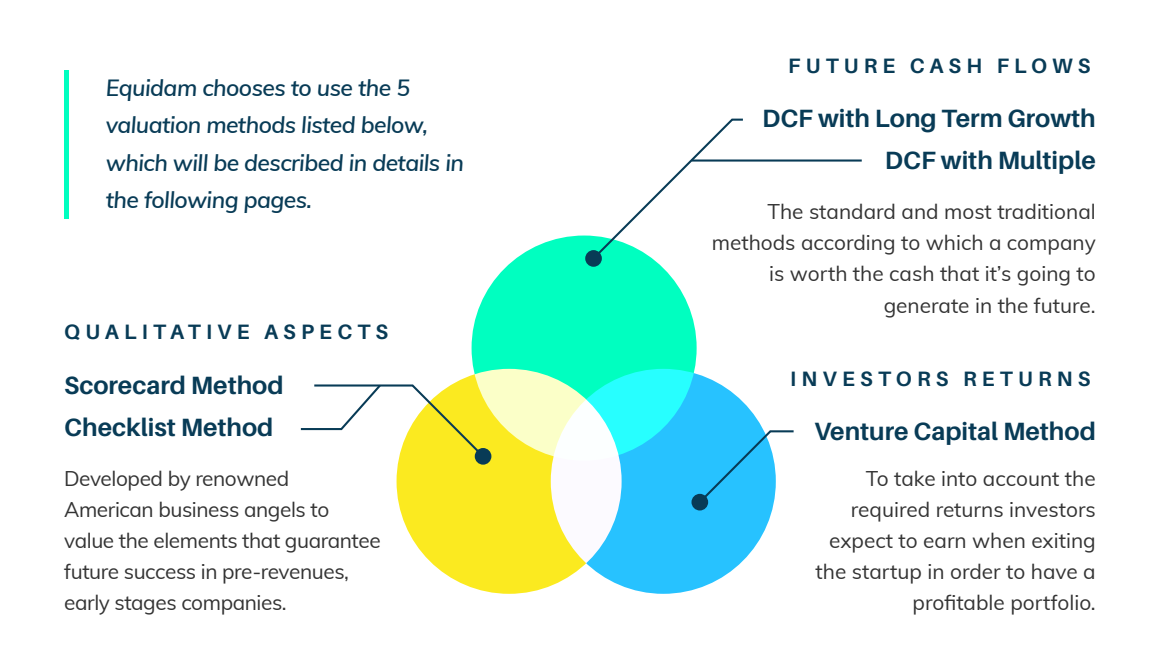

Filtering out the less suitable approaches leaves a core set of methods considered more practical and insightful for startup valuation. We can identify four such methods: the Scorecard method, the Checklist method, the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method, and the Venture Capital (VC) method. Our methodology leverages these four, employing two distinct variations of the DCF approach, resulting in a five-method framework designed to provide a balanced perspective.

Qualitative Insights: Scorecard & Checklist Methods

Rationale: For very early-stage companies, particularly those pre-revenue or with limited traction, quantitative data like financial projections are highly speculative. In these phases, the qualitative attributes of the venture often serve as the best available indicators of future potential. Methods that systematically assess these factors are therefore crucial. They evaluate foundational elements like the team’s capability, the market opportunity’s scale, and the product’s defensibility, which are predictive of future success. We utilize two such methods, both developed by experienced angel investors.

- Scorecard Method (Bill Payne / Ohio TechAngels):

- Concept: This method evaluates a startup by comparing it against the average pre-money valuation observed for similar companies within the same region, sector, and stage of development. The startup is scored on several key qualitative criteria, and these scores determine an adjustment factor (positive or negative) applied to the average peer valuation. Its development is attributed to the work of angel investors, notably Bill Payne of Ohio TechAngels, and it has been endorsed by organizations like the Kauffman Foundation.

- Checklist Method (Dave Berkus):

- Concept: Developed by prominent angel investor Dave Berkus, the Checklist method (also known as the Berkus method) takes a different qualitative approach. Instead of comparing to an average, it typically starts with a maximum potential pre-money valuation deemed achievable for a startup of that type in its region. Value is then assigned based on the startup’s progress across several key areas or ‘building blocks’, essentially discounting from the maximum based on achievements. Unlike the Scorecard, it doesn’t explicitly benchmark against competitors but focuses on the startup’s internal milestones and risk mitigation. The original Berkus method assigned up to $500,000 for each of five factors, but modern adaptations, including ours, often use a data-driven maximum regional valuation as the starting point.

Quantifying the Future: The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Method

- Concept: The DCF method is often considered the most theoretically sound approach to valuation. Its premise is that a company’s value is equal to the sum of all its expected future free cash flows, discounted back to their present value to account for the time value of money and the risk associated with receiving those cash flows. Free cash flow to equity (FCFE) is typically used, representing cash available to equity holders after all expenses, investments, and debt payments.

- Strengths & Challenges for Startups: The strength of DCF lies in its theoretical rigor and its ability to model the specific financial drivers of a business. However, its application to startups is challenging due to the heavy reliance on long-term financial projections, which are inherently uncertain and speculative for young companies with limited or no operating history. The valuation outcome is highly sensitive to key assumptions, including future growth rates, the discount rate used to reflect risk, and the terminal value calculation representing the company’s worth beyond the explicit forecast period. This sensitivity can lead to the “garbage in, garbage out” problem if assumptions are unrealistic or manipulated.

- Making DCF Work for Startups: Despite these challenges, DCF can be a valuable tool, particularly when assumptions are made transparent and become a basis for negotiation between founders and investors. We incorporate several adjustments to make the DCF method more robust and relevant for the startup context:

- Survival Rates: Recognizing the high failure rates among startups, we explicitly discount projected future cash flows by a survival rate. This rate, often based on statistical data for companies at similar stages, represents the probability that the startup will still be operational to generate the cash flow in that specific future year. This directly incorporates the existential risk faced by early-stage ventures.

- Illiquidity Discount: Shares in private companies are not easily traded, meaning investors cannot quickly exit their position if needed. This lack of liquidity represents an additional risk. We apply an illiquidity discount to the calculated present value of cash flows, reducing the valuation to reflect this risk. This discount is often based on academic research (e.g., by Prof. Aswath Damodaran) and typically ranges from 10% to 40% depending on company specifics.

- Discount Rate (Cost of Equity): The rate used to discount future cash flows reflects the riskiness of the investment. We calculate the cost of equity using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). This incorporates the risk-free rate, a market risk premium specific to the company’s country, and Beta ($\beta$). Beta measures the volatility of the company relative to the market. We use an adjusted Beta that considers not just industry but also company stage, size, and profitability, drawing on research by Damodaran. Due to the typically non-tradable nature of startup debt, We assume the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is equal to the cost of equity.

- Equidam’s Two DCF Variants: A key element of our methodology is the use of two distinct DCF methods, differing primarily in how they calculate the Terminal Value (TV) – the value of the company beyond the explicit forecast period (typically 3-5 years). This dual approach provides robustness and acknowledges different potential long-term scenarios:

- DCF with Long-Term Growth (DCF-LTG): This is a standard, widely used DCF variation. It assumes that after the explicit forecast period, the company will survive and grow its free cash flows at a stable, constant rate indefinitely. This long-term growth (LTG) rate is typically modest, based on the industry, and constrained by the overall economic growth rate (e.g., we use a range of 0.1% to 2.5%). The terminal value is calculated using a formula similar to the Gordon Growth Model, representing the present value (at the end of the forecast period) of these perpetually growing cash flows.

- DCF with Multiple (DCF-Exit Multiple): This variant assumes the company is sold or exits at the end of the explicit forecast period. The terminal value is estimated by applying a market-based multiple to a financial metric of the final projected year. We typically use an industry-specific EBITDA multiple (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) applied to the projected EBITDA in the last forecast year. These multiples are derived from public market data or sources like Damodaran’s research. This approach reflects a potential market exit scenario rather than perpetual growth.

By employing both DCF-LTG and DCF-Multiple, the methodology provides a range reflecting different plausible futures – one where the company matures into a steady grower, and one where it achieves an exit based on prevailing market conditions. This avoids over-reliance on a single, uncertain long-term assumption. Furthermore, the systematic inclusion of survival rates and illiquidity discounts directly addresses key startup risks within the DCF framework, making it more practically applicable and defensible for early-stage ventures compared to standard DCF applications. This bridges the gap between theoretical valuation principles and the specific risk profile of startups.

The Investor’s Lens: The Venture Capital (VC) Method

- Concept: The VC method is a pragmatic approach widely used by venture capitalists and other investors in private companies. It directly incorporates the high return expectations required by VCs to compensate for the significant risk inherent in startup investing and the likelihood of failures within their portfolio. The method works backward from a potential future exit: it estimates the company’s value at a projected exit date (e.g., 3-7 years in the future) and then discounts that value back to the present using a high target rate of return (ROI) specific to the startup’s stage. Unlike DCF, it typically ignores interim cash flows, focusing solely on the entry valuation and the expected exit value.

The VC method provides a vital perspective grounded in the economic realities of the venture capital industry. It answers the critical question from an investor’s standpoint: “What is the maximum price we can pay today to achieve our required return, given a plausible exit scenario?” This differs from DCF’s focus on intrinsic value. A significant divergence between the VC method valuation and those from other methods can signal a potential misalignment between the founder’s view of the company’s worth and the return potential required by investors. By using stage-specific required ROIs, the method also implicitly prices the evolving risk profile of the startup throughout its lifecycle, demanding higher potential returns for higher perceived risk at earlier stages.

The Power of Synthesis

Rationale for Multiple Methods

Startup valuation is inherently complex and uncertain. Relying on a single valuation method can provide a narrow or potentially biased view. Best practices in valuation, particularly for private and early-stage companies, advocate for the use of multiple methods. Analyzing a company from different angles – considering its qualitative strengths, its intrinsic value based on future cash flows, and its attractiveness based on investor return requirements – leads to a more comprehensive, reliable, and defensible assessment of value. This approach helps to triangulate a reasonable valuation range and reduces the risk of being misled by the limitations or specific assumptions of any single technique. Some research even suggests that using multiple methods correlates with better investment performance.

Equidam’s 5-Method Approach

Recognizing these benefits, we employ a blended methodology that integrates five distinct valuation methods. These methods are grouped into three core perspectives to ensure comprehensive coverage:

- Qualitative Aspects: Assessing the foundational strengths and risks, crucial in early stages.

- Scorecard Method

- Checklist Method

- Future Cash Flows: Estimating intrinsic value based on projected financial performance (the traditional academic view).

- DCF with Long-Term Growth (DCF-LTG)

- DCF with Multiple (DCF-Exit Multiple)

- Investor Returns: Evaluating the opportunity from the perspective of venture capital economics.

- Venture Capital (VC) Method

Stage-Based Weighting

Stage-Based Weighting

The final valuation we present is not a simple average of the five methods. Instead, it is a weighted average, where the contribution of each method to the final result is adjusted based on the company’s stage of development. This dynamic weighting is a critical feature, acknowledging that the relevance and reliability of different valuation drivers change as a company matures:

- Early Stages (e.g., Idea, Development, Pre-Seed, Seed): In the earliest phases, when financial track records are minimal or non-existent and future projections are highly uncertain, qualitative factors are paramount. Therefore, the Scorecard and Checklist methods receive higher weights. They provide insights based on the team’s strength, market opportunity, product development, and other observable attributes.

- Later Stages (e.g., Growth, Maturity): As a company establishes a market presence, generates revenue, and develops a more predictable financial history, quantitative methods become more reliable and relevant. Consequently, the weights shift towards the DCF methods (both LTG and Multiple). Financial projections are now grounded in actual performance, making cash flow analysis more meaningful. At the Growth and Maturity stages, we eliminate the qualitative methods entirely, as the value of team and assets becomes better reflected in their impact on cash flows.

- VC Method Weight: The Venture Capital method, reflecting the investor’s required return perspective, tends to maintain a relatively consistent weight across most stages where venture capital is relevant, though the required ROI input itself changes significantly by stage.

This stage-based weighting system ensures the valuation methodology adapts to the evolving information landscape of a startup. It prioritizes the most relevant and reliable indicators of value at each phase of the company’s journey, from the qualitative potential of an early idea to the quantifiable performance of a scaling business.

Benefits of the Blend

This sophisticated, multi-method, stage-weighted approach aims to deliver a balanced and practical perspective on value. It integrates:

- Qualitative Strengths: Capturing early indicators of success via Scorecard and Checklist.

- Intrinsic Value: Estimating fundamental worth based on future cash generation via DCF methods.

- Market Benchmarks: Incorporating market data through peer comparisons (Scorecard/Checklist) and exit multiples (DCF-Multiple, VC Method).

- Investor Requirements: Reflecting the economic realities of venture investing via the VC Method.

The outcome is designed to be a “practical and useful, understandable perspective on value”, moving beyond simplistic measures. Furthermore, the variance observed between the results of the different methods allows us to estimate a valuation range, providing useful context and flexibility for negotiations. By standardizing this comprehensive approach and delivering it through an accessible online platform, complex valuation techniques become available to founders who might otherwise lack access, potentially empowering them in funding discussions.

Comparison of Equidam’s 5 Methods

| Method Name | Perspective | Key Inputs | Primary Focus | Primary Stage Relevance (Weighting) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scorecard | Qualitative | Questionnaire, Peer Avg. Valuation (Market Data) | Comparison to average peers | Highest in Early Stages |

| Checklist | Qualitative | Questionnaire, Peer Max. Valuation (Market Data) | Achievement vs. max potential | Highest in Early Stages |

| DCF with LTG | Quantitative | Financial Projections, Discount Rate, LTG Rate | Intrinsic Value (Perpetuity) | Highest in Later Stages |

| DCF with Multiple | Quantitative | Financial Projections, Discount Rate, Exit Multiple | Intrinsic Value (Exit Scenario) | Highest in Later Stages |

| VC Method | Investor Returns | Financial Projections, Exit Multiple, Required ROI | Investor Return Potential | Relevant Across Stages (Pre-Maturity) |

This comparison highlights how each method contributes a unique perspective, collectively forming a more robust valuation picture than any single method could provide alone.

Aligning Founders and Investors

Beyond the Number

While arriving at a valuation figure is necessary for structuring a deal, its greater value often lies in the process itself. The discussions, debates, and analysis undertaken during the valuation exercise can be more beneficial in the long run than the final number agreed upon. It serves as a critical mechanism for communication and alignment between founders and potential investors.

Focus on Assumptions

At its core, any forward-looking valuation is built upon a set of assumptions about the future – market growth, customer adoption, cost structures, competitive responses, exit possibilities, and associated risks. The valuation process forces both founders and investors to articulate, scrutinize, and potentially challenge these underlying assumptions. Disagreements about valuation often stem from differing views on these fundamental inputs. Making these assumptions explicit allows for a more focused and productive negotiation, centered on the key drivers of the business’s potential success or failure. The goal becomes finding consensus on the most likely future scenario and the associated risks and opportunities, rather than simply arguing over a price tag.

Facilitating Alignment

Our methodology and platform are explicitly designed to support this constructive dialogue. Key features facilitate alignment:

- Transparency: The methodology is clearly detailed, with reports showing the calculations, parameters, and data sources for each of the five methods. This demystifies the “black box” of valuation.

- Explicit Parameters: Key inputs like discount rates, survival rates, multiples, and qualitative scores are clearly presented, allowing them to be discussed and understood.

- Adjustability: The platform allows users (founders or advisors preparing for negotiation) to adjust parameters and assumptions if necessary, seeing the immediate impact on the valuation outcome. This enables scenario analysis and helps identify the most sensitive assumptions.

- Structured Framework: By providing a comprehensive report covering multiple perspectives, it grounds the negotiation in an assessment of fundamental potential rather than letting it be driven solely by market hype, fear of missing out (FOMO), or negotiation leverage.

In essence, the platform functions as a structured communication tool. It translates the abstract concept of ‘value’ into a concrete set of calculations based on explicit inputs. This framework provides a common language for founders and investors, enabling them to dissect the valuation, debate specific assumptions (like growth rates or market size), and collaboratively refine the picture of the company’s future. This process can lead to fairer deals struck in a more sustainable manner. Furthermore, engaging deeply with the assumptions behind the valuation fosters a more profound, shared understanding of the business model, risks, and strategic priorities. This deeper alignment, cultivated during the valuation process itself, can lead to better-informed investment decisions and stronger, more collaborative founder-investor relationships, ultimately contributing to more efficient capital allocation and potentially improving the startup’s long-term prospects.

External Support

Expert commentary and academic research often echo this view, emphasizing that in early-stage venture deals, the valuation process serves critical functions beyond price discovery. It acts as a due diligence tool, a framework for strategic discussion, a test of founder assumptions, and a mechanism for building consensus and trust between parties. The negotiation around valuation becomes a negotiation around the shared vision for the company’s future.

Using Comparables Wisely

The Right Role for Multiples

While using comparable transaction multiples as the primary driver of valuation for startups is problematic, these multiples do have an appropriate and valuable secondary role: benchmarking. Once a comprehensive valuation has been established using robust, multi-faceted methods (like our five-method approach), one can calculate the implied multiples from that valuation (e.g., Valuation / Annual Recurring Revenue, or Valuation / EBITDA). These implied multiples can then be compared against the multiples observed for peer companies in the market. This provides valuable context and a market-based sanity check on the primary valuation result. We facilitate this by providing benchmark data from a large dataset of private companies, allowing users to compare their valuation, revenue growth, and EBITDA growth against relevant peers filtered by industry, stage, and geography.

Interpreting Benchmark Differences

Comparing the startup’s implied multiples to those of its peers can offer insights. For instance, if the valuation results in an implied revenue multiple significantly higher than the peer average, it suggests that the underlying valuation assumptions reflect a belief in superior future growth prospects, profitability, or strategic positioning for the company compared to its competitors. Conversely, a lower multiple might suggest expectations of slower growth or higher risk. However, interpretation requires nuance; cash flow generation (better approximated by EBITDA multiples) is ultimately what drives long-term value, so revenue multiples alone don’t tell the whole story.

Contrast with Misuse

This post-valuation benchmarking starkly contrasts with the flawed approach of using average market multiples as the direct input to determine the valuation in the first place. The benchmarking approach uses the comprehensive valuation to understand the company’s relative position in the market, while the flawed primary approach lets crude market averages dictate the company’s assessed worth, ignoring its specific fundamentals. This distinction is crucial. Using implied multiples derived from a detailed valuation as a sanity check reverses the problematic logic of using market multiples to drive the valuation. It allows for market context without letting potentially misleading averages override the fundamental assessment of the specific venture.

Key Lessons for Valuing Startups

Navigating the complexities of startup valuation requires a nuanced understanding of appropriate methodologies and the purpose of the valuation exercise itself. Key takeaways include:

- Focus on Practical Methods: While numerous valuation methods exist, only a subset is truly practical for early-stage, high-growth startups. The Scorecard and Checklist methods offer structured ways to assess crucial qualitative factors. Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) methods, when adapted for startup risks (survival rates, illiquidity), provide insights into intrinsic value based on future potential. The Venture Capital (VC) method offers a critical reality check based on investor return requirements.

- Embrace the Blended Approach: No single method captures the full picture. Utilizing a combination of methods, as with our five-method, stage-weighted approach, provides a more robust, reliable, and defensible valuation by integrating qualitative insights, quantitative projections, and investor perspectives.

- Prioritize Assumptions: The valuation number is an output; the inputs and assumptions are where the real substance lies. Focus negotiation and discussion on the underlying drivers – market size, growth rates, cost structure, risks, exit potential. Alignment on these assumptions is key to reaching a mutually agreeable valuation.

- View Valuation as a Strategic Tool: The valuation process is more than just a prerequisite for fundraising. It’s an opportunity to critically assess the business model, refine strategic plans, identify key risks, and articulate the company’s value proposition and future potential more effectively to investors and other stakeholders.

- Demand Transparency: Seek out valuation methodologies and tools that are transparent about their calculations, inputs, and data sources. This transparency facilitates understanding, builds trust, and enables the constructive dialogue necessary to reach a fair valuation and build a strong founder-investor relationship. Valuation should illuminate, not obfuscate.

By understanding these principles and leveraging appropriate methodologies, founders and advisors can approach valuation negotiations with greater confidence and work towards outcomes that fairly reflect the company’s potential while meeting the requirements of investors.

Stage-Based Weighting

Stage-Based Weighting