Price vs Value (Part 1): The Momentum Trap in VC

Venture capital has long been about finding and funding the next big success. But in today’s market, the distinction between price and value in VC has grown stark, which is causing even greater headaches in the pursuit for liquidity.

A recent conversation between Peter Walker of Carta and Beezer Clarkson of Sapphire Ventures underscored this point – especially around the issue of secondaries (selling startup equity early) and why early liquidity can feel uneasy when a company’s true worth is uncertain. In a climate where paper valuations soar but actual outcomes lag, venture capitalists (VCs) and their backers (LPs) must grapple with whether high prices reflect genuine value.

“Imagine you took a secondary out of a company that raised a couple of priced rounds in quick succession. Based on what we’ve seen in 2021 and beyond, there’s no guarantee that company ends up being worth anything. So you took cash out of a thing that ended up at zero […] but taking it out that early causes some uneasiness… Am I taking cash out of a thing that’s still ephemeral, I don’t really know what it is?”

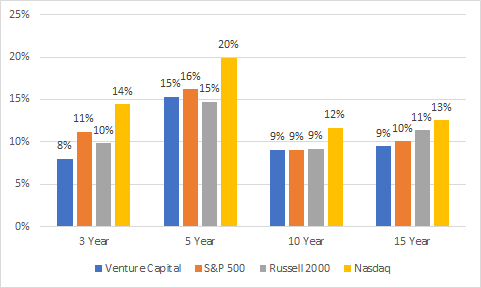

Here we will explore how venture investing has shifted toward pricing games, the consequences of “financialising” VC, and why a return to fundamentals may be due. We’ll also consider the role of LPs in pushing the industry back toward value-based discipline, reinforced by insights from the Kauffman Foundation’s notable 2012 report on venture returns vs. public markets.

When Early Liquidity Feels Uneasy – The Secondaries Dilemma

Walker and Clarkson’s discussion raised a key tension: taking some money off the table early versus holding on indefinitely for a potentially bigger payoff. Historically, selling equity in a thriving private company before an IPO was almost taboo – a sign of lack of conviction. As Walker joked, “VCs talking about 2021: really wish we had taken some liquidity out during that hype cycle. VCs talking about AI investments now: selling early is lame, concentrate into the winners, hold forever!”. The culture in venture often frowns on early sales as short-sighted. But reality is forcing a rethink.

What makes these secondary sales uneasy is the discrepancy between a startup’s last priced valuation and its actual value as determined by a less euphoric market. Walker pointed out that the challenge is not simply normalizing secondaries as an exit option, but normalizing them at a sometimes steep discount to the on-paper valuation. In other words, when a fund sells shares on the secondary market, buyers often demand a large discount – a tacit acknowledgment that the previous valuation (set during a frothy funding round) was too high.

There are “two elephants in the room,” according to veteran investor Dave McClure: many portfolio companies are still overvalued, not yet marked down from their 2020–21 bubble-era rounds, and even for companies with more reasonable recent rounds, secondary buyers will still pay less than the last mark to compensate for illiquidity. In essence, secondary market pricing reveals what VCs don’t like to admit – the real value might be lower than the paper price. Yet, many general partners (GPs) resist this truth, especially if they’re in the middle of raising new funds and don’t want to show losses.

Early liquidity, therefore, creates an internal conflict. On one hand, selling some shares can deliver returns to LPs and de-risk a position; on the other hand, it may expose that the touted unicorn valuation is somewhat of a mirage. No wonder many GPs feel queasy about secondaries. As McClure summarized, GPs know they should “mark down their portfolios / accept lower prices to get cash,” but are “highly unmotivated to admit this to their LPs” during fundraising. The result: VCs often keep companies private and ride out valuations as long as possible, even if it means delaying or avoiding liquidity events that would reveal a more sober valuation.

How VC Became a Game of Marks

Why has this gap between price and value widened? The evolution of venture capital over the past two decades provides context. A series of regulatory and market shifts have tilted the industry toward pricing strategies – chasing high valuations – sometimes at the expense of underlying value creation.

In the late 1990s, the National Securities Markets Improvement Act (NSMIA) of 1996 opened the floodgates for more private capital. NSMIA relaxed onerous state “blue sky” laws, making it easier for companies to raise money from out-of-state investors and allowing non-traditional players (like mutual funds and hedge funds) to invest in private rounds. Suddenly, startups could access large pools of capital without going public. Shortly after, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002, while aimed at improving public-company governance, had the side effect of increasing costs and scrutiny for IPOs. Many young companies chose to stay private longer rather than face the heavy compliance burden of SOX. The number of IPOs plummeted in the 2000s, and the time to IPO stretched out. It was no longer 3-5 years from founding to IPO; it became 10+ years in many cases.

Then came the low-interest-rate era following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. For roughly 15 years (2009 through 2021), capital was historically cheap – a Zero Interest-Rate Policy (ZIRP) world. This drove huge amounts of money into venture capital as investors hunted for yield and growth. Tech startups benefitted from a “free money” environment that made growing without immediate profits seem easy. The result was an explosion of unicorns (startups valued at $1B+) and ever-higher prices set in funding rounds. By 2020–2021, venture valuations reached record highs in both deal size and frequency, fueled by this abundant capital and FOMO frenzy.

Critically, many of these valuations were driven by momentum and competition among investors, not by fundamental business performance. As one Axios analysis recently put it, numerous unicorns are now “finally accepting that their ZIRP-era valuations were inflated”. In other words, the price tags assigned during the free-money boom don’t always reflect the companies’ real value in a normalized market.

This shift toward price over value has been gradual but profound. Venture capital in the 20th century was often about investing early, nurturing companies, and realizing value upon exit (IPO or acquisition). In the 21st century, especially the 2010s, it increasingly became about marking up companies through successive private rounds. With IPOs delayed, a company’s valuation might be “proven” not by public markets but by the next VC who pays more than the last. Post-NSMIA and in the era of mega-funds, the private market essentially created its own pricing mechanism – one that sometimes divorced price from economic reality.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in late-stage venture. Bill Gurley, a prominent VC at Benchmark, sounded the alarm back in 2015: flooding “immature private companies” with huge sums in late-stage rounds can have perverse effects, such as eroding discipline and pushing profitability further into the future. Companies raised hundreds of millions on market hype, often postponing the proof that their business models actually work. The value – sustainable profits, efficient operations, competitive moats – was presumed to materialize eventually, but the price was taken up-front. It was as if venture capital began treating incremental pricing metrics themselves as the product.

Three factors – regulatory changes, a glut of private capital, and near-zero interest rates – thus enabled the venture industry’s pricing boom. VC firms could raise larger funds and deploy capital faster; startups could remain private and keep raising at higher prices without the reality check of public markets; and everyone was chasing growth over profits in a low-rate environment. This set the stage for the industry’s next evolution: the financialisation of VC, where fund managers optimized for paper returns and interim metrics, sometimes to the detriment of long-term value creation.

When Paper Returns Trump Reality

One of the most consequential shifts in venture has been the emphasis on financial metrics like IRR and TVPI – numbers that reflect interim, on-paper gains – over ultimate returns like DPI (cash back to investors) or actual company outcomes. In a financially driven model, a startup doesn’t even need to exit to make a VC fund look successful; it just needs to raise another round at a higher valuation (thus boosting the fund’s mark-ups on paper). This phenomenon has aligned with VCs’ short-term incentives, but it carries hidden risks.

Consider the typical VC fund economics. A venture firm usually charges a 2% management fee and takes 20% carry (profit share). Over a fund’s 10-year life, those 2% annual fees are guaranteed income, while the 20% carry is only earned if the fund actually returns profits. Unsurprisingly, many managers have acted more like asset gatherers than diligent capital allocators. As the Kauffman Foundation observed, “too many [VCs] are compensated like highly-paid asset managers” rather than solely for investment performance. Most of their income comes from the “2” of the 2-and-20, not the “20,” which means raising larger funds (and collecting more fees) can become an end in itself.

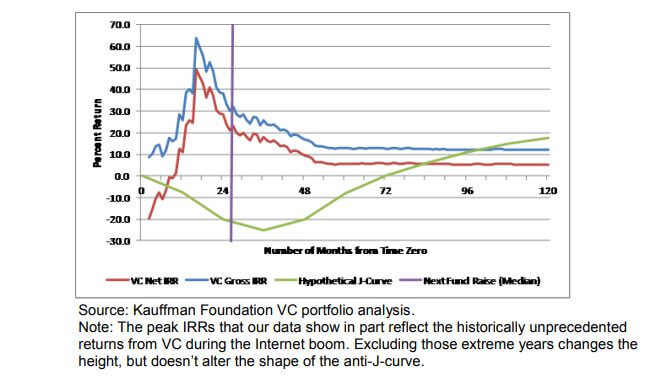

This fee-driven motive creates a subtle but powerful incentive: inflate short-term returns (on paper) to raise the next fund quickly. The sooner a VC can show a high IRR or multiple on invested capital, the sooner they can go back to LPs for a bigger fund – restarting the fee cycle. Kauffman’s analysis of its own portfolio revealed an “n-curve” of net IRR, where performance peaked around month 16 of a fund – exactly when GPs typically start fundraising for the next fund. Those early “returns” weren’t realizations at all; they were driven by unrealized valuation increases that GPs assign to their own holdings. In other words, paper gains spiked early (coinciding with new fund pitches), then often petered out over time as reality caught up.

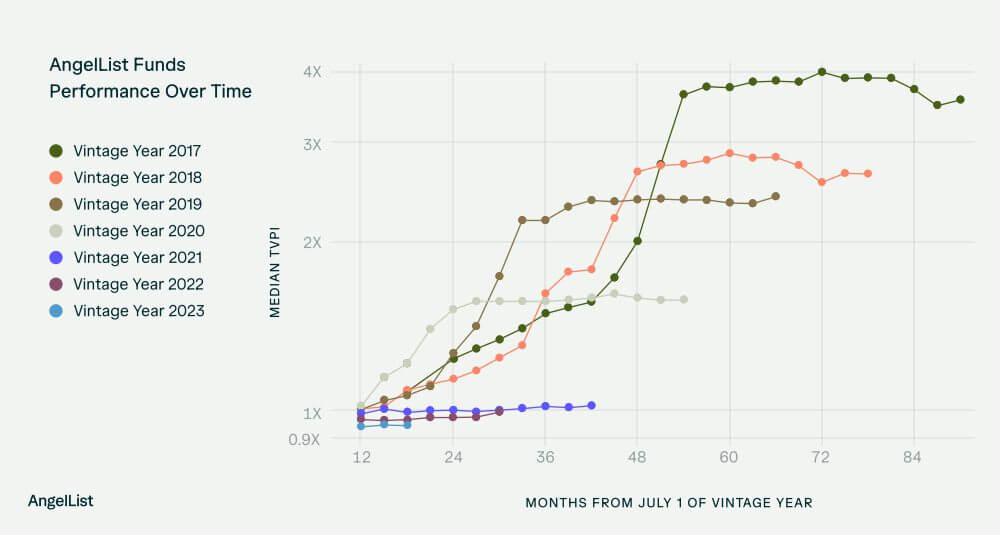

For example, TVPI (Total Value to Paid-In) includes the market value of unrealized investments, whereas DPI (Distributions to Paid-In) tracks actual cash returned. For funds raised in the late 2010s, TVPIs were often several multiples, but DPIs remained shockingly low. For example, the median 2017 vintage VC fund, eight years on, has a TVPI of 3.57× yet a DPI of only 0.29×. That means the typical fund still hasn’t even returned 30% of investors’ capital, despite showing over 3× “value” on paper. VC portfolios are sitting on “hefty paper markups without seeing enough exits to return even half of what limited partners put in”.

This is a classic manifestation of price vs. value: high valuations boosting the numerator of TVPI, but few liquidity events to generate DPI. Eventually, those funds must find exits – selling companies to acquirers or via IPO – or else face writing down those optimistic valuations. As last year’s AngelList’s annual report warned, sooner or later funds will be “forced to start cutting their view of the value” of holdings if exits don’t materialize. Indeed, 2025 is shaping up as a “crucible moment” that will reveal whether those lofty valuations hold or if reality forces a reckoning.

How did we get here? Financialisation in VC meant adopting behaviors more akin to hedge funds or Wall Street, focusing on metrics that drive short-term optics and fundraising ability. Key symptoms include:

-

Obsessing over IRR (internal rate of return). IRR can be juiced by quick markups or early exits, even if final outcomes disappoint. Some VCs “flip” companies or mark them up fast to show a high IRR, since a high IRR in year 2–3 helps raise the next fund. Kauffman found that the traditional 10-year J-curve (slow start, big finish) had morphed into a spike-and-flat “n-curve” – net IRR peaking by month 16, then often declining as funds aged and struggled to turn paper gains into cash.

-

Maximizing TVPI over DPI. It’s common to see funds boasting a 2× or 3× TVPI long before they’ve returned anything significant. Total value can include highly illiquid, maybe overvalued stakes. By downplaying DPI (which may only come much later, if at all), GPs emphasize the appearance of great performance. In effect, mark-ups become the metric.

-

Keeping companies private longer to maintain the illusion of performance. This has been a self-reinforcing cycle. Since VCs aren’t pressured to exit, they can hold companies private and raise consecutive funds on the back of rising paper valuations. In turn, they have an incentive not to rush to exit – especially if an exit might reveal a lower value. As discussed in the Data Minute podcast, some GPs know they will eventually need to accept lower prices for liquidity, they are in no hurry to do so “while attempting to raise new funds”. Thus, startups remain private as unicorns (or “soonicorns”) far longer than in the past, and funds delay converting TVPI to DPI. The game can continue until a fund’s end-of-life or LPs start demanding distributions.

-

Growing fund sizes and “venture bank” behavior. Larger funds mean more fee income, period. Many VC firms discovered that scaling up assets under management was easier and more immediately rewarding than consistently producing top-quartile returns. This has given rise to what I refer to as “venture banks” – mega-firms that operate almost like investment banks or asset managers, deploying huge sums across many stages, often with less sensitivity to valuation. They can pay higher prices to win deals, confident that their platform and capital base will carry them through. In practice, these large firms sometimes even manufacture liquidity to justify marks – for example, selling small secondary stakes of a hot company at peak frenzy (locking in some DPI while the market is hot) or arranging for one portfolio company to acquire another to show an exit. Such maneuvers can “muddle through” enough DPI to claim victory, even if the bulk of the holdings remain illiquid.

The overall effect of financialisation is that many VCs have become experts in managing prices – i.e. valuations and fund metrics – rather than in creating enduring value through company-building. We now have a generation of venture investors whose track record is rich with markups but relatively poor in exits. As the saying goes, “you can’t eat IRR.” Limited partners ultimately depend on DPI – cash returned – to meet their own obligations (pensions, endowments, etc.). But the current system has often rewarded VCs for piling up high valuations and interim IRRs, allowing them to collect fees and raise successive funds, all while deferring the question of whether those valuations will hold water in the end.

When Exits Test Price vs. Value

Sooner or later, the music stops. Exits – whether via IPO or M&A – are the ultimate test of a venture-backed company’s value. Unlike private fundraising, which can sometimes be driven by hype, relationships, or momentum investing, exits usually involve outside buyers with a more unforgiving view of value. Public market investors scrutinize revenues, growth rates, and profitability. Strategic acquirers (like big tech companies) evaluate synergies and ROI. In both cases, an inflated private valuation can quickly be humbled by a dose of market reality.

We’ve seen this starkly in recent years. During the 2020–2021 boom, dozens of unicorns rushed toward public markets via IPOs or SPAC mergers, often to disappointing results. Companies like WeWork (attempted IPO in 2019) or more recently various fintech and internet startups in 2021 learned that public investors wouldn’t simply endorse the last private price. In 2022–2023, the IPO window essentially shut, leaving overvalued unicorns in limbo. Many chose to wait, hoping to “grow into” their lofty valuations rather than face a down-round IPO. As Axios’s Dan Primack reported, for the past two years most unicorns delayed going public to avoid valuation haircuts – partly to protect founder morale and avoid the stigma of a “down IPO”. The attitude was, if we just hold on, maybe we’ll hit those targets with another year or two of growth.

By mid-2025, however, a tentative reopening of the IPO market has shown that reality cannot be deferred forever. A number of high-profile unicorns have bitten the bullet and gone public at adjusted (lower) prices – and tellingly, the market has rewarded them for finally pricing realistically. For example, Circle, a fintech company, was another company to IPO at a valuation below its last VC round; Omada Health went public only slightly above its prior valuation. Chime, a digital bank, also took a haircut from its $25B valuation in 2021. Other companies like Hinge Health and eToro have already gone public at valuations below their peak private marks. This may sound like bad news, but it’s actually a healthy development – these companies are accepting market reality, and in several cases their stocks have performed well post-listing (investors appreciate the honesty of a fair price).

On the M&A side, we see a similar story. Some unicorns, unable to sustain their paper valuations, have sold for much less to strategic buyers. A recent Crunchbase analysis notes that many exits “did not appear to provide much in the way of returns” relative to prior valuations. For instance, Noname Security, a cybersecurity startup, had raised at a unicorn valuation in 2021 but sold in 2023 for around $450 million – a clear markdown from its once billion-dollar price tag. Another example is Candy Digital, an NFT startup that achieved unicorn status during the crypto frenzy, but was acquired by a smaller company in 2023 for an undisclosed sum (almost certainly far below $1B). These outcomes reinforce that price is what you pay, value is what you get: many unicorns of the ZIRP era simply weren’t worth what the peak prices implied.

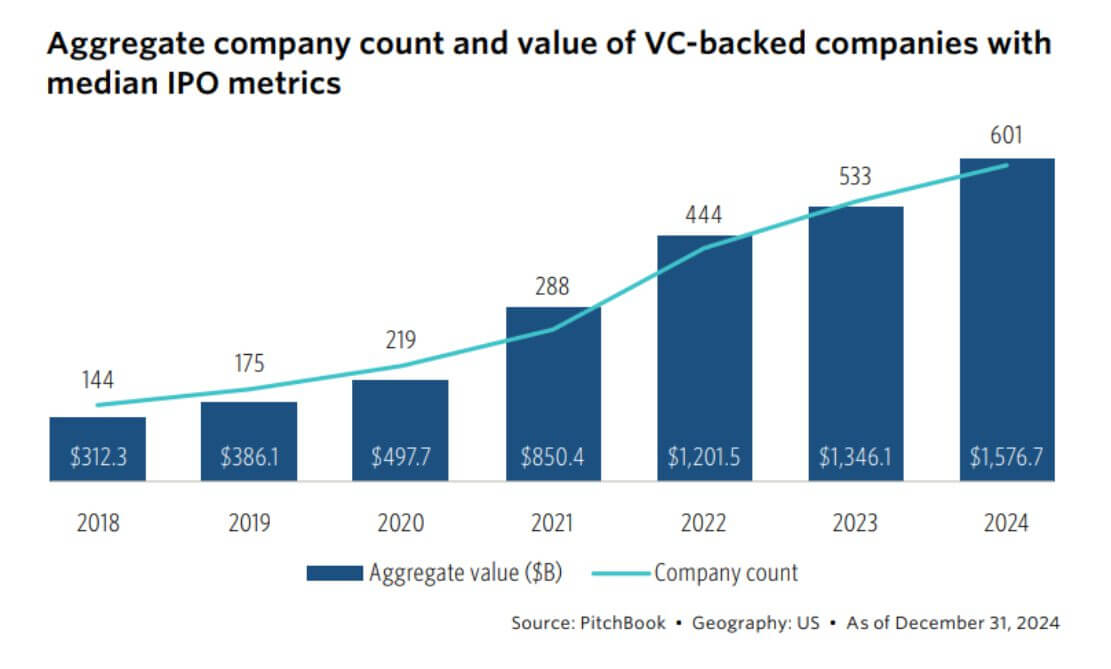

As of May 2025, Crunchbase data indicated that at the recent pace of exits, it would take 30 years for all U.S. unicorns to either IPO or be acquired. (A year prior, that backlog was an astonishing 49 years – so while things have improved, there remains a long line of startups needing liquidity.) This “unicorn backlog” signals a couple of concerns. First, many richly valued companies are stuck – they haven’t found exit opportunities commensurate with their valuations. Second, it suggests that a lot of supposed “value” in VC portfolios is still just theoretical. If an entire portfolio is waiting for an IPO window to open to realize gains, it implies those companies might not be attractive enough in normal conditions – they require a boom-time market to exit. Relying on rare liquidity windows (when public market sentiment is euphoric) is a precarious strategy. It works for a while – as seen in 2020–21 when a wave of IPOs and SPACs bailed out many – but when the window closes, you’re left holding a bag of marked-up investments that can’t be easily cashed out.

Crucially, the longer companies stay private, the more their valuation narratives face real tests. A startup can carry a $10B valuation on paper, but if its financials support only a $2B valuation in the public market, sooner or later that gap will close – either through a down round, a down IPO, or an internal write-down. We are seeing VCs and founders come to terms with this now. Finally accepting inflated valuations and taking the medicine of a reset is painful, but necessary for the ecosystem to move forward. For limited partners, who in many cases have been waiting a decade for distributions, the hope is that honesty in pricing will lead to actual liquidity, even if it’s at lower multiples than hoped. Some cash return is better than endless paper gains.

What about those companies that still refuse to test the market? Unfortunately, the concern is that many are over-cooked – propped up by ever-extended private funding and perhaps not built to thrive under public scrutiny. While staying private, startups avoid the harsh spotlight where all and sundry are able to sift through the weak spots of your model. In private, one can maintain “deficiencies” out of view and keep market value high. But once public, any weakness gets punished by stock sell-offs. This is exactly why venture banks prefer to keep companies private longer: to avoid that scrutiny and keep valuations buoyant as long as possible. The downside is, it delays the inevitable and perhaps allows more fundamental rot (unit economics issues, bloated cost structures) to set in. By contrast, an earlier exit can impose discipline – or at least reveal which emperors have no clothes.

In summary, the return of IPOs and uptick in acquisitions in 2024–2025 are bringing a long-needed valuation reality check to venture portfolios. When price meets value, it can be a reckoning. But it’s also healthy: it separates the truly valuable companies from those that were merely riding the wave. For VCs, this is a moment of truth – a chance to prove that their paper returns can convert to real returns, or else to confront the mistakes of the bubble and adjust accordingly.

Venture Banks vs. Venture Capitalists

Underlying all these trends is a structural split in the venture capital world. It’s becoming increasingly clear that there are two distinct strategies at play:

-

On one side, the financialised mega-funds – the “venture banks” – which behave like large asset managers. They raise giant multi-stage funds, deploy capital at scale, and often prioritize growth and market share over immediate profitability in their portfolio companies. These firms (exemplified by the likes of Andreessen Horowitz, SoftBank’s Vision Fund, etc.) can dictate pricing in the market due to their firepower. They often exploit structural advantages to win deals: extensive platform teams offering services to startups, the ability to alleviate signaling risk by backing companies through many rounds, networks of “scout” or partner funds that feed them deals, star operator partners that attract founders, and a general insensitivity to price (they can afford to pay top dollar to secure a stake). Venture banks “sell” LPs on consistency and access – they aim to deliver a steady flow of deals and markups, behaving almost like an index of the tech market. These players have pulled in vast amounts of capital from new classes of LPs, effectively replacing some public market funding with private capital to avoid scrutiny. The trade-off, however, is that this shift has coincided with mediocre returns. The influx of big money and the resulting competition have been a negative influence on VC returns over the last 20 years. In short, venture banks prioritize scaling AUM and staying in every hot deal – their business model is about being omnipresent and capturing upside across a broad front, even if that means paying high prices and accepting lower per-deal returns.

-

On the other side, the traditional, smaller VC firms – let’s call them venture capitalists in the classic sense. These are firms that often cap their fund sizes to maintain focus, take a “high-conviction, high-touch” approach with startups, and are more selective about deals and valuations. Examples frequently cited include Benchmark and Index Ventures, which explicitly keep their funds smaller and refuse to chase every trend. They see being “people-focused” and constraint on size as a feature, not a bug. Such firms ought to skip the overhyped arenas where a venture bank has set the terms. (For instance, Benchmark and Index largely sat out the crypto craze of the last decade, whereas Andreessen Horowitz raised over $7.5B across crypto funds in six years.) Traditional VCs tend to invest where they have an edge in understanding and nurturing a business – they are less likely to engage in valuation wars on “consensus” hot deals. Instead, they might focus on sectors or stages that are out of the spotlight, where valuations are more reasonable and the potential for outsized value creation is higher. Their strategy hinges on finding the truly exceptional startups (the outliers) and helping them grow sustainably, rather than assembling a huge index of companies.

This bifurcation has serious implications. The venture banks, with their war chests, have reshaped the early-stage landscape in some ways: they can outbid or squeeze out smaller managers on popular deals, and they can flood zones like AI or fintech with capital, driving up prices. If a firm like a16z zeroes in on a sector, they often squeeze out other managers who aren’t as well capitalised or connected. Competing head-to-head with them on their terms (high price, fast pace) is usually a losing proposition for a traditional VC. Therefore, the strategies diverge: big venture banks play a volume and momentum game; traditional VCs play a focus and patience game.

For LPs (limited partners) allocating money to venture, this split offers a clear choice. Do you back the mega-funds that promise access to every top deal (at the cost of paying top prices and perhaps getting average-like returns)? Or do you back smaller funds that aim for concentrated bets and potentially higher alpha (but may miss out on some trendy deals and can’t deploy as much capital)? In recent years, many LPs chose the former, lured by brand-name firms and the idea of “one-stop” exposure to tech. This contributed to the concentration of capital under large VC franchises, arguably to the detriment of overall returns. However, if those franchises continue to underperform public markets (or even fail to return capital in a timely way), LP sentiment could swing back to favoring disciplined, value-driven venture investing.

It’s worth noting that some industry insiders see the venture banks as an evolution, possibly a permanent change. Perhaps venture is maturing into an asset class that resembles private equity – dominated by a few big players with lots of capital, and a long-tail of niche specialists. If that’s the case, maybe mega-funds and boutique funds will coexist, each with their role. But others argue that something has been lost in translation: that the essence of venture capital – backing innovative founders early and helping them create real value – has been diluted in the era of venture banks.

From a price vs. value perspective, the venture bank model is heavily tilted toward price. These firms are often price-insensitive (they’ll pay 100× revenue for a startup if they believe it’s a land-grab) and justify it by the network effects of being in the big deals. Traditional VCs, in contrast, worry more about value – they ask whether a company is actually worth the price tag based on its market, team, product, and traction. They might walk away from an overhyped deal because they don’t see a realistic path to a good return from that valuation. In doing so, they risk looking foolish if the company keeps rising, but they protect their downside. Over a full cycle, that discipline can pay off.

We’re essentially seeing venture investing split into two games: one game is asset management (venture as an asset class to be scaled and financially engineered), and the other is venture craftsmanship (venture as picking and building winners). The former excels in bull markets when capital is plentiful and markups come easy; the latter shows its mettle in more challenging times when careful selection and company-building matter more.

Re-aligning Price with Value

If there’s a silver lining in the current market environment, it’s the opportunity – even the necessity – for venture capital to return to fundamentals. A prolonged tech downturn or lower liquidity environment forces everyone to refocus on what really creates value: strong business models, customer traction, sustainable growth, and prudent financial management. For VCs, this means shifting from a “growth at any price” mentality back to a “value investing” mentality (albeit in the context of high-growth startups).

What might a fundamentals-first approach look like in VC? A few guiding principles emerge from the commentary of experienced investors:

-

Focus on DPI (cash returns), not just TVPI. Ultimately, investors can’t spend paper gains. Venture firms that pride themselves on delivering actual liquidity back to their LPs will stand out. That means seeking exits when they make sense, and not overstaying an investment’s welcome just to keep marking it up internally. It may also mean valuing secondaries as a tool – taking some chips off the table in a disciplined way. Rather than viewing secondary sales as “lame,” savvy VCs can use them to return capital and de-risk positions (for example, selling a small stake of a winner at a high price to lock in a win, while still keeping most upside). The key is that distributions should start to flow earlier and more regularly, instead of waiting 10-12 years for a big bang that may never come.

-

Underwrite new investments based on valuation sanity, not price momentum. In practical terms, this means doing the harder work of assessing a startup’s realistic future cash flows or strategic value, and determining what price today would allow for a healthy return. It means not simply assuming some greater fool will pay double the valuation in 18 months. If a deal is too expensive to make sense, discipline says you pass – even if it’s a hot company. A reasonable entry price provides a margin of safety and more upside if the company succeeds. In contrast, momentum investing – paying whatever it takes because “everyone else is in it” – often leads to later write-downs. Traditional VCs can differentiate by walking away from the consensus “bonfire” of overhyped deals. Instead, they look for less obvious opportunities: companies or sectors that aren’t the current darlings but have solid potential on a slightly longer horizon. That might mean investing in areas that will become crucial after the current trend plays out (the “skate to where the puck is going” philosophy).

-

Recognize and nurture the outliers. The power-law nature of venture hasn’t changed – a few big winners drive most of the returns. What needs to change is identifying those winners based on real indicators, not just who can raise at the highest valuation. VCs returning to fundamentals will spend more time on due diligence, understanding customer love, product differentiation, market timing, etc., to spot the startups that have a shot at genuine long-term dominance. Then they will support those companies with resources and advice to grow intelligently. It’s a return to the craft of venture investing: building company value, not just bidding up company price.

-

Manage fund size and strategy intentionally. As the adage goes, “your fund size is your strategy.” A fundamentals-focused VC likely should not run a $1 billion early stage fund and make a handful of concentrated bets. They might opt for more reasonable fund size to make higher multiples attainable, and build a reasonably diversified portfolio to manage risk. This aligns interests as well – smaller funds have to produce real returns to move the needle (they can’t live forever on management fees alone). In fact, the 2012 Kauffman report recommended exactly this: backing VC funds under $400 million. The idea is that smaller, more focused funds and better alignment on carry make for more disciplined, value-driven investing. We are already seeing some LPs gravitate back to boutique venture firms that fit this profile, in search of alpha.

-

Use data, but stay grounded in reality. Today’s VCs have far more data at their fingertips – market benchmarks, cohort analyses, etc. – and that’s a good thing if used wisely. It can help avoid wishful thinking. Likewise, understanding public market comparables should inform private valuations. If public SaaS companies trade at 6× revenue, a private startup at 50× had better have a very unique story (and maybe that story won’t hold up).

There are signs that parts of the industry are indeed tilting back toward fundamentals. Some high-flying startups have refocused on efficiency and profits (often at the behest of their investors). Venture fund pitch decks are touting DPI returned or portfolio revenue growth more than just paper markups. LPs are asking tougher questions about realized track records. This is healthy. It hearkens back to what venture capital is supposed to do: fund the building of valuable companies, not just create financial instruments.

Traditional VCs may actually benefit by zigging when the mega-funds zag – by looking for the opportunities that aren’t crowded with easy capital. In practice, that could mean targeting sectors that have fallen out of favor (and thus carry lower valuations) but have strong long-term prospects, or geography/stage niches that big funds overlook. It could also mean doubling down on core competencies like enterprise software or healthcare, where deep expertise can yield outsized value, rather than chasing whatever theme is hottest this year.

Demanding Discipline and Transparency

Limited partners – the pensions, endowments, family offices, and fund-of-funds that bankroll venture capital – hold significant power to shape industry behavior. For a while, many LPs were content to ride the boom, accepting opaque reporting and trusting top-tier VCs even as overall returns lagged. The Kauffman Foundation’s report was a wake-up call highlighting LPs’ complicity in venture’s dysfunction. Now, as the cracks in the price-centric model are evident, LPs can push for change by simply insisting on what any rational investor should: real returns, prudent strategy, and transparency.

The report made several strong recommendations that are just as relevant today: negotiate lower fees and better alignment, demand more transparency into fund economics, measure performance against public benchmarks, and be pickier about which funds deserve capital. In the decade since, some progress was made – for instance, many LPs do look at PME (Public Market Equivalent) metrics now, and some have shifted allocations to smaller or newer funds that demonstrate skill. Yet, the allure of big-name firms and the fear of missing out on the next big thing often kept money flowing into the largest funds, even as returns disappointed. Kauffman’s analysis of its own portfolio found that over 20 years, the foundation’s VC funds, net of fees, had only returned 1.31× invested capital on average (a dismal outcome, barely above break-even). Moreover, 78% of the funds Kauffman was in failed to beat a simple index of small public stocks (even by a modest 3% annual premium). In other words, nearly four-fifths of those VC funds would have been better off if Kauffman had just bought publicly traded equities and done nothing – a damning statistic. This underperformance wasn’t solely due to bad luck; Kauffman concluded it stemmed from structural issues: too-large fund sizes, misaligned incentives, and LPs chasing brand names without due diligence.

Going forward, LPs can help correct the price-value imbalance by adopting a more discerning stance:

-

Allocate based on merit, not momentum. This means resisting the urge to pour money into a fund just because it’s raised by a celebrity VC or is oversubscribed. Instead, scrutinize the actual returns that fund (or GP) has delivered historically, especially DPI and PME metrics. If a firm has sky-high TVPIs but very low DPI, ask the hard questions: what’s the path to realization? How conservative are the valuations? As Reuters noted in a piece on venture’s troubles, institutional investors should behave “a bit more like investors, and a bit less like chumps being bullied into throwing millions of dollars into a series of opaque black boxes delivering decidedly subpar returns”. In practice, that means sometimes saying “no” to re-upping with a fund that hasn’t earned it, or walking away from VC as an asset class if it doesn’t fit the portfolio’s goals.

-

Insist on transparency and governance. LPs have the right to know basic things like how much GPs are taking in fees and salary, how valuations are determined, and how reserves are managed. It’s astonishing that some LPs will invest in a VC fund with less scrutiny than they would invest in a public security. Kauffman pointed out this irony: investors would never accept a public company with no disclosure on executive pay or financials, yet they “happily invest in venture funds” with minimal transparency. This must change. If a VC wants an LP’s capital, they should be prepared to share detailed information (under NDA if needed) about the health of the portfolio. LPs can negotiate for advisory board seats, regular updates, and clawback provisions that ensure fair play. Strong governance can prevent GPs from gaming the system too egregiously (for example, marking up companies beyond reason or extending fund life endlessly without returning cash).

-

Reward the behaviors that create value. If an LP observes that a particular fund manager consistently distributes cash early and does so by selling companies at good multiples (even if that means some “uncool” trade sale or an IPO in an unsexy sector), they should lean into that manager. Conversely, if a manager is known for just raising larger and larger funds with flashy paper gains but no realizations, the LP should deprioritize or drop them. Over time, this capital allocation will shift the industry. In essence, LPs must signal: we care about DPI and true ROI, not your headline valuation of Company X. Some progressive LPs now explicitly ask for TVPI-to-DPI conversion statistics – basically, how much of your paper returns have you actually realized? This is a great practice, as it forces GPs to confront their own scorecard.

-

Be patient but hold accountable. Venture is a long game, and LPs know this. But patience has limits. It’s reasonable for an LP to expect that by year 7 or 8 of a fund, some significant liquidity has been achieved (barring extraordinary market events). If a fund is a decade old and still mostly unrealized, that should be a red flag in the absence of a very good explanation. By holding GPs to their word on timelines and return expectations, LPs can discourage the indefinite private-market “extend and pretend” strategy.

Finally, LPs might consider innovative fund models that align price with value. For example, some have advocated for performance-based fees (as opposed to fixed 2%) – where the management fee might step down or up depending on interim DPI or other value milestones. Others suggest segmented funds where the late-stage portion has different terms (reflecting its lower risk/return profile) than the early-stage portion. The goal of all these ideas is to ensure GPs are working to create real value because that’s how they’ll be rewarded, rather than simply accumulating more assets.

It’s worth recalling that the venture capital model has been very successful in the past at creating enormous value – when incentives and discipline align. Many of the world’s most valuable companies were nurtured by VCs who combined vision with rigor. They paid reasonable prices, helped the founders through rough patches, and took them public when the time was right (or sold to the right acquirer). Those VCs earned fabulous returns and built lasting businesses. That is the model to strive for, not the more recent model of growth-at-any-cost leading to disappointing endgames.

As we navigate this period of correction, one hopes that both VCs and LPs will internalize the lessons. High price does not equal high value. True value eventually shines through – whether higher (in the case of a well-founded company that was undervalued) or lower (in the case of an overhyped one that couldn’t deliver). The venture ecosystem is healthiest when prices approximate value, allowing capital to flow to the best ideas without veering into speculative excess. Achieving that equilibrium will require restraint, courage, and yes, sometimes saying no to a “hot deal” or a superstar fund if the numbers don’t justify it.