The recent IPO performances of companies like Chime and Circle have reignited conversations about market timing and the significance of first-day “pops” in public offerings. As venture capitalists and founders debate whether these dramatic opening-day gains signal a favorable IPO window, the underlying data tells a more complex and counterintuitive story.

The conventional wisdom suggests that a strong IPO pop—where shares surge on their first day of trading—demonstrates robust market demand and creates positive momentum for the company. However, a deeper analysis reveals that optimizing for maximum first-day gains may actually be detrimental to long-term shareholder value and company success.

Getting the Price Right: The Google Standard

In contrast to the pop-chasing approach, the best performing IPOs typically have a modest price increase on day-one. This indicates they were well priced, didn’t leave much money on the table, and still had healthy demand.

Research supports this counterintuitive finding: companies that analyzed returns of U.S.-listed IPOs since 2010 found that those that popped between 10 and 20 percent on their first trading day have the highest returns to date, of 111 percent. IPOs that popped between 0 and 10 percent on day one have current return of 69, and those that popped over 20 percent have a current return of 55 percent.

Google’s 2004 IPO serves as the gold standard for this approach. By using a Dutch auction mechanism instead of traditional book-building, Google captured fair market value for the company rather than subsidizing investment bank clients. The result was a modest first-day gain and exceptional long-term performance for all shareholders.

From Going Dutch: The Google IPO:

The decision to use a modified Dutch auction complemented Google’s vision and long-term strategy: to be innovative and creative, while providing value for its investors, employees, and customers.

The Institutional Incentive Problem

Understanding why IPOs are systematically underpriced requires examining the misaligned incentives in the traditional offering process. When investment banks manage IPO pricing through book-building, they essentially set prices for their own institutional clients, who then profit from the immediate arbitrage opportunity.

Circle’s recent IPO exemplifies this dynamic: “

Circle sold 39 million shares, raising $1.145 billion after underwriting fees of $67 million. Had the shares fetched the $107.5 close on June 6 instead of the $31 (excluding fees) paid in the presale by the likes of mutual and hedge funds, the company and insiders combined would have collected $4.144 billion. Hence, as of the second day of trading, the IPO had left a staggering $3 billion on the table.

This represents one of the largest wealth transfers from company shareholders to investment bank clients in modern IPO history—$3 billion in value that could have funded years of additional growth and innovation.

The Venture Capital Complicity

The persistence of this system isn’t merely due to founder inexperience or market inefficiency. Venture capital firms often actively encourage underpricing through two well-documented mechanisms:

Analyst Lust: VCs will collude with investment banks to trade initial underpricing for favorable coverage up until the lockup expiry. This relationship benefits VCs who plan to exit quickly but harms the company’s long-term prospects.

We find that top VCs are much more likely to receive all-star coverage. This coverage is not contingent on bank affiliation at the time of the IPO because all banks wish to make top VCs happy to potentially reap future business. We find that non-top VCs are no more likely to garnish all-star coverage than non-VC backed IPOs. We demonstrate that IPOs backed by top venture capital firms that receive allstar coverage are significantly more underpriced, regardless of the affiliation of the underwriter.

Grandstanding: Young VC firms are willing to bear the cost of higher underpricing in IPO exits and to accept a lower premium in M&A exits to build their reputation. The prestige of working with prestigious investment banks and achieving dramatic pops helps VCs raise subsequent funds, regardless of the cost to their portfolio companies.

Young venture capital firms take companies pubic earlier than older venture capital firms in order to establish a reputation and successfully raise capital for new funds. Evidence from a sample of 433 IPOs suggests that companies backed by young venture capital firms are younger and more underpriced at their IPO than those of established venture capital firms.

Research confirms this misalignment: “when VCs, especially top VCs, have a large equity position in a firm, their main goal is to exit as quickly as possible at the highest possible price, whereas the firm founders are likely focused on a much longer-term horizon”.

Alternative Approaches: Lessons from the Market Leaders

The most successful companies have demonstrated that alternatives to the traditional IPO process can deliver superior outcomes:

Direct Listings: Companies like Spotify and Slack have successfully bypassed investment banks entirely, allowing existing shareholders to sell directly to public market investors. While this approach requires strong brand recognition and operational maturity, it eliminates the systematic underpricing problem.

Dutch Auctions: Google’s pioneering use of this mechanism demonstrated that price discovery through competitive bidding can achieve fair valuations while maintaining broad access for all types of investors.

Both approaches prioritize long-term value creation over short-term trading profits, aligning with the interests of companies building sustainable businesses.

Market Timing Is a Myth

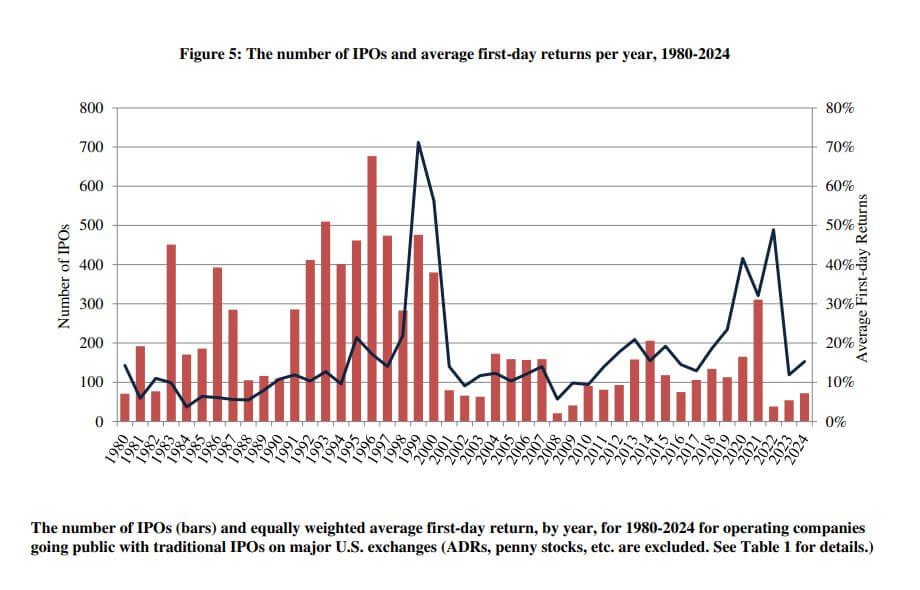

The data reveals another crucial insight: the best companies do not look to list during an IPO window. In fact, IPO windows are connected with low quality listings that underperform over time.

High-volume IPO periods, often celebrated as favorable market conditions, actually correlate with poor long-term performance. Research shows that “IPOs issued during the high-volume period are more likely to have worse performance on average than those issued during other periods”.

The implication is clear: quality companies go public when they’re ready operationally and financially, not when market sentiment appears favorable. The companies waiting for the “right market conditions” are often those that need external validation because their fundamentals don’t speak for themselves.

From Essays On Ipo Cycles And Windows Of Opportunity:

IPO market has significant time variations over time and IPOs issued during the highvolume period are more likely to have worse performance on average than those issued during other periods. Conventional wisdom tend to argue that the high failure rate of IPOs issued during the “hot” period is due to lower screening standard, lower required return on equity, or overoptimistic investors.

A Framework for IPO Success

For companies considering going public, the evidence points toward several key principles:

Price for Value, Not Validation: Aim for fair pricing that reflects the company’s intrinsic worth rather than maximizing first-day gains. A 10-20% opening pop indicates optimal pricing—enough to show healthy demand without leaving excessive money on the table.

Consider Alternative Structures: Evaluate direct listings or Dutch auction mechanisms, especially if the company has strong brand recognition and doesn’t need the marketing benefits of a traditional roadshow.

Align with Long-Term Partners: Choose investment banks and advisors whose incentives align with long-term value creation rather than short-term trading profits.

Ignore Market Timing: Focus on operational readiness, financial sustainability, and strategic clarity rather than trying to time market cycles.

The Path Forward

The IPO market doesn’t have a problem—companies do. There has been a “poor-quality company” problem where so many private unicorns became fat and sloppy during the period of low-interest-rates.

The solution isn’t waiting for better market conditions or chasing bigger pops. It’s building companies that can succeed in public markets through operational excellence, sustainable unit economics, and clear paths to profitability.

The best companies recognize that an IPO is not a financing event or an exit strategy—it’s a transformation into a public company that will be judged on long-term value creation. They approach going public as Google did: with confidence in their fundamentals, respect for all shareholders, and a commitment to capturing fair value for the business they’ve built.

In an era where many private companies remain trapped by inflated valuations and unsustainable business models, this approach represents both a competitive advantage and a return to first principles. The companies that embrace it will find that the public markets, far from being inhospitable, reward genuine value creation with sustainable, long-term success.