Secondary transactions are sales of existing shares, by founders, employees, angels, or fund investors, to new or existing holders. Unlike a primary round, no new shares are issued and no cash enters the company; rather, ownership changes hands. Secondaries come in several flavors: founder‑ or employee‑led sales (direct, platform‑mediated, or issuer‑run tender offers); GP‑led processes where a fund rolls a prized asset into a continuation vehicle; and LP‑led trades where institutions sell or buy stakes in funds. For companies, well‑designed secondaries can support retention, alignment, and cap‑table hygiene; for sellers, they provide diversification; for buyers, scarce exposure to high‑conviction names. This essay explains the role of founder‑led secondaries, weighs their pros and cons, surfaces pitfalls and best practices, and situates them within the broader 2025 secondary market.

The state of secondaries in 2025

After a choppy 2022–2023 reset, 2025 is the year liquidity professionalized and scaled. Dedicated secondary capital is abundant, tender programs grew in frequency and size, and pricing bifurcated: elite names (especially in AI, space, and fintech infrastructure) often clear near last‑round marks or at modest premia, while legacy 2021–2022 cohorts continue to trade at meaningful discounts. Bid‑ask spreads tightened, and buyers have become more selective but faster to commit when governance and disclosure are institutional‑grade.

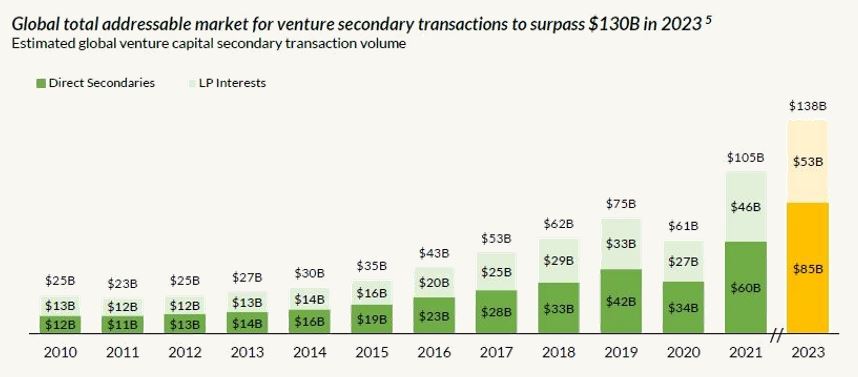

Global secondary volumes (fund‑level and venture alike) set fresh records in the first half of 2025; company‑run liquidity windows expanded sharply through 2024 and into 2025; and multiple venues report a shift toward premium pricing for top‑decile companies. Platform data shows narrower spreads and more balanced buyer–seller interest, reflecting healthier two‑way markets. Meanwhile, high‑profile employee tenders at category leaders (AI, payments, space) created anchors for fair value and normalized broad‑based liquidity.

Three forces explain the rise: (1) longer private lifecycles (IPO window open but selective), (2) more dedicated capital for secondaries (including semi‑liquid/evergreen vehicles) and (3) better rails: issuer‑led tenders, auction mechanisms, and (in the UK) intermittent trading frameworks that enable controlled windows. Inside companies, CFOs and boards now treat liquidity like a recurring operating process with templates, guardrails, and calendars.

Top‑quality companies with strong growth and clean preference stacks can transact near the last round or at modest premia; others still clear at discounts that reflect preference overhang and profitability timelines. Cohort effects matter: businesses last financed at 2021 peaks typically see steeper discounts; those with 2024–2025 rounds face smaller gaps. Across platforms, bid‑ask spreads compressed to multi‑year lows, a sign of maturing price discovery.

What this means for founders.

- Plan on annual or semiannual, issuer‑run windows with standardized disclosures and blackouts; they’re the fairest way to reach many sellers without information asymmetry.

- Price from the waterfall and current performance, not headlines. Use competition (bookbuilds/Dutch auctions) to support fairness.

- Treat buyer selection as a risk control: concentration limits, standstills, and limited info rights keep governance clean and prevent gray‑market churn.

The Role of Founder‑led Secondaries

Founder‑led secondaries are a simple idea that touches every sensitive nerve in a startup: alignment, governance, valuation, and culture. In a primary financing the company issues new shares for cash; in a secondary, existing holders (founders, early employees, or angels) sell their shares to new or existing investors. No new money hits the balance sheet, but real money reaches the people who took early risk. Done well, secondaries convert illiquid paper into measured, values‑consistent liquidity without compromising the company’s trajectory. Done poorly, they can become a lightning rod that undermines trust.

Secondaries matter because venture timelines lengthened. Teams are staying private longer, and compensation plans designed for five‑year exits now need to sustain motivation for eight to ten. Meanwhile, later‑stage investors increasingly expect professional governance, predictable disclosures, and periodic liquidity rather than a single cliff‑edge IPO. Founder‑led secondaries sit at the intersection: they can be the relief valve that keeps founders focused and the glue that retains key employees, while also broadening the shareholder base with long‑term, less interventionist capital.

The role of a secondary is therefore not merely transactional; it is strategic. It can signal durability to recruits (“we run structured, fair programs”), reduce single‑asset risk for founders without implying diminished commitment, and create room on the cap table for the right kind of investors: those who will not demand board seats or invasive information rights for a minority stake. For growth‑stage companies, the most effective stance is to treat liquidity as a program, not a one‑off exception: align with the board on a cadence (annual or semiannual), eligibility (who can sell and how much), and rails (issuer‑coordinated tenders/auctions, or tightly controlled bilateral sales). When liquidity is normalized, it ceases to be gossip‑worthy and becomes just another part of a professional private‑company operating system.

Finally, founder‑led secondaries play a governance role: they force the company to clarify transfer restrictions, co‑sale and ROFR mechanics, information‑sharing policies, and insider‑trading blackouts. They also push leadership to model the liquidation waterfall behind the headline valuation, which is healthy discipline for board discussions about performance and capital allocation.

The Pros and the Cons

Pros

- Measured liquidity without dilution. The most obvious benefit is personal diversification. Founders who have banked a modest portion of paper gains typically make better long‑term decisions; they can take rational bets, pass on suboptimal acquisition offers, and continue building. Because the sale is of existing shares, there is no dilution to the company’s other shareholders or to employees’ future option grants.

- Retention and recruiting. Clear, recurring liquidity windows communicate that the company respects the economics of its people. Senior hires from public tech are more likely to join, and stay, if they know there’s a path to realizing value before an exit. Structured tenders that include employees can be a powerful cultural signal, especially when participation is tied to vesting and performance.

- Cap‑table hygiene and strategic investor mix. Secondaries allow you to curate who owns your company. You can consolidate dozens of small holders into a single SPV, admit crossover or secondary specialists who accept limited rights, and enforce standstills that prevent activism. The result is a cleaner ledger, fewer surprises, and more aligned long‑term partners.

- Signaling and market discipline. A well‑run program with a consistent disclosure pack, clear eligibility rules, and credible price discovery, tells the market (current and future) that the company understands its obligations to minority shareholders. It can even help triangulate fair value for internal planning by anchoring conversation around actual clearing prices rather than aspirational headlines.

- Operational leverage. Once the templates, workflows, and communications kit exist, repeating the program is far easier than spinning up bespoke bilateral deals every time an executive has a life event. Platforms and administrators reduce KYC/AML friction, standardize documentation, and streamline funds flow.

- Tax and planning flexibility. Founders and long‑tenured employees can coordinate sales with favorable tax treatments in their jurisdiction or with rollovers and trust planning. Even when tax is neutral, the liquidity allows better personal risk management without tapping leverage.

Cons

- Optics and alignment risk. The single biggest risk is perception: large founder cash‑outs, especially pre‑PMF or without a parallel primary raise, can look like a vote of no confidence. That perception can cascade: employees may wonder whether to sell too, investors may slow walk future support, and the press may misinterpret the signal. Even when everyone is aligned internally, the outside world may not see the nuance.

- Valuation and waterfall complexity. Founders often hold common stock while investors own preferred with liquidation preferences and other rights. Pricing common off the last preferred round without modeling the preference stack is a recipe for disputes. If down‑round or flat scenarios are plausible, common may be worth far less than headline EV implies.

- Accounting and compensation knock‑ons. Issuer‑organized secondaries near the last preferred price can influence 409A (US) or UK FMV used for option pricing. That can increase strike prices for new grants and change equity comp expense (ASC 718). If you don’t plan the appraisal cadence around the program, you may inadvertently raise the cost of compensation.

- Process and regulatory burden. Multiple sellers, a fixed price, and a defined window can trigger tender‑offer rules in the US; large block purchases may require antitrust filings. In the UK, stamp duty applies to many share transfers. Cross‑border cap tables add KYC/AML complexity and settlement nuances. All of this is manageable, but it turns an improvised “quick sale” into a project with a real calendar.

- Cap‑table sprawl and future governance risk. If you don’t control the buyer mix, you may end up with activist‑inclined minority holders or an unreadably dense register that slows every approval. Poorly drafted side letters (or none at all) can come back to bite you when investors claim rights you did not intend to grant.

- Time cost and distraction. The CEO, CFO, legal, and HR teams will spend real cycles. If the company is in the middle of a major launch or fundraising, the opportunity cost can outweigh the near‑term benefits.

The conclusion is not that secondaries are risky by nature; it’s that the risks are design problems. Thoughtful structure, sequencing, and communications neutralize most of them.

The Pitfalls

- Selling too much, too soon

Oversized founder sales, especially before clear product‑market fit or defensible unit economics, send the wrong message. Avoid the temptation to “catch up” with a single, large disposal. Instead, stage liquidity in modest tranches tied to milestones. Pair founder sales with employee eligibility where possible, and with a concurrent primary raise if runway messaging matters. - Ignoring the preference overhang

Headlines celebrate post‑money valuations; waterfalls decide who actually gets paid. Failing to model liquidation preferences, participation features, and accrued dividends is the fastest way to misprice a program and to create resentful buyers or sellers. Always build a simple as‑converted cap table with a waterfall tab and stress‑test bear/base/bull outcomes. - Accidental tender offers

If you invite many sellers, state a fixed price, and constrain the window, you may have created a tender offer without meaning to — bringing formal notice, timing, and withdrawal‑rights obligations. Engage counsel early to choose the right path: true tender, bookbuild with price discovery, or bilateral transfers routed through ROFR/co‑sale mechanics. - 409A and payroll surprises

A near‑par tender can pull option FMV upward. If your next option grant batch is scheduled for the week after close, you may unintentionally raise strike prices and reduce perceived value for new hires. Plan your valuation updates and grant calendars around the program, and ensure payroll is ready for any employee withholding on proceeds. - Cap‑table clutter

Allowing dozens of micro‑buyers to appear on the register makes every future consent harder. Use SPVs or designate a single nominee where appropriate. Enforce concentration limits and require side letters that cap information rights, forbid board seats, and include standstills and transfer restrictions. - Late discovery of filings and taxes

Antitrust thresholds, stamp duties, securities‑law exemptions; none of these should be a closing‑week surprise. Create a pre‑flight checklist that screens transactions for filing triggers and tax frictions in every relevant jurisdiction. - Information asymmetry and MNPI leakage

If some sellers or buyers receive richer data than others, you invite fairness challenges and regulatory risk. Standardize the disclosure pack, set a data cut‑off date, keep a Q&A log visible to all participants, and run trading blackouts for insiders. - Unclear internal messaging

If employees hear about the program in the press or through rumor, you lose trust. Draft the internal announcement first, explain eligibility and taxes plainly, and train managers to handle predictable questions.

Best Practices

- Design for alignment

Start with “why now?” and write it down. Typical answers: retention, diversification, cap‑table hygiene, or investor rotation. Propose eligibility objectively (role, tenure, vesting status) and set per‑person and aggregate caps. Milestone‑linked caps are defensible and fair. Make founders subject to the same rules as everyone else. - Choose the right rails

For small, targeted sales, bilateral transfers may suffice, but route them through the company’s ROFR and consent processes. For anything broad, an issuer‑organized tender or auction with a standardized disclosure pack is safer and fairer. Consider a stapled primary + secondary if optics or runway are concerns; it aligns sellers’ liquidity with fresh capital entering the business. - Institutionalize information control

Prepare a lightweight but consistent disclosure pack: charter/articles, cap table (as‑converted), stock plan docs, high‑level KPI deck, and risk factors. Set a data cut‑off and avoid piecemeal updates mid‑process. Use NDAs, log all Q&A, and keep the pack available to all eligible participants to minimize information asymmetry. - Price from the economics

Anchor to the last preferred round only after running the waterfall and updating performance. For broader programs, favor competitive price discovery (bookbuild or Dutch auction) over a purely negotiated fixed price. Where common is being sold, articulate the rationale for any discount to preferred; preference overhang, lack of information rights, and transfer restrictions are legitimate drivers. - Protect the cap table

Set concentration limits for any single buyer. Prefer investors who accept no incremental board seats, limited or no information rights beyond existing, and contractual standstills. Use an SPV or nominee to keep the register tidy when many small sellers participate. Prohibit quick re‑trades that could create a gray market in your stock. - Run a real calendar

Treat the program like a financing. A practical ten‑week cadence is: (1) board alignment and legal scoping; (2) prepare disclosures and onboard administrator; (3) launch window and collect indications; (4) price and allocate; (5) close, settle, update registers; (6) complete post‑deal valuation. Publish the dates internally. Traveling the company with a short FAQ will save you dozens of one‑off conversations. - Coordinate tax, accounting, and grants

In the US, sync with your 409A provider; in the UK, coordinate with HMRC valuation practices and payroll. Time major grant batches for after you’ve updated FMV. Provide employee tax clinics or office hours; even simple guidance on withholding and filing reduces anxiety and errors. - Communicate like adults

Lead with purpose and fairness. Say plainly that participation is optional, eligibility is objective, and the company will not tolerate information games. Thank sellers for their early risk, and buyers for supporting long‑term building without governance creep. After close, publish a short post‑mortem internally: what worked, what will change next time, and when the next window is likely. - Make it a program, not an exception

The first time is the hardest. After that, you have templates for side letters, stock transfer agreements, allocation rules, and timelines. Set a default cadence (for example, a small annual window) with the board. When liquidity is predictable, it stops being a distraction and becomes part of how a modern private company operates. - Measure what matters

Track retention around windows, employee satisfaction, cap‑table concentration, and the variance between indicated and clearing prices. Use those metrics to refine eligibility, caps, and buyer selection. Over time, the program should get cleaner, faster, and less contentious. - The bottom line

Founder‑led secondaries are neither a moral hazard nor a panacea. They are a governance tool. Use them to align incentives, professionalize your private‑company market, and keep your team focused on compounding value. If you design for optics, price from economics, and execute with institutional discipline, secondaries will support, and not distract from, the mission you set out to achieve.

The role of tender offers

Tender offers are the issuer‑organized version of secondary liquidity: the company (or an affiliate) makes a time‑bound offer to buy or facilitate the purchase of shares from many holders at a single, stated price (or through a Dutch auction) with a defined window and settlement process. In the US, formal tender‑offer rules usually apply (meaning minimum offer periods, withdrawal rights, proration if oversubscribed, standardized disclosures, and tight MNPI controls) which is why tender offers tend to feel more like a financing than a casual resale. For high‑profile private companies, they have become the default way to serve broad employee and founder liquidity while protecting fairness and information symmetry. Recent, widely reported examples include Stripe, which has run recurring employee liquidity tenders (alongside limited company repurchases) at successively higher marks, and SpaceX, which routinely runs semiannual tenders allowing employees to sell to approved investors.

How tender offers differ from other secondary sales: unlike bilateral transfers, tender offers centralize price, documentation, and compliance, reducing the risk of unequal information or missed consents. Unlike ad‑hoc platform‑brokered listings, tender offers are company‑led, typically cover many sellers at once, and end with a single clearing price and clean cap‑table updates (often via proration and concentration limits). They also create a clearer anchor for 409A/UK FMV processes and internal planning because they reflect an organized, widely accessible market check rather than a one‑off negotiation. The trade‑offs are calendar discipline, heavier admin, and potential external optics — so they work best when framed as a recurring, rights‑respecting program rather than a one‑time “cash‑out.”

The role of GP‑led secondaries

In a GP‑led secondary, the general partner (your VC/PE fund manager) creates a continuation vehicle to acquire one (single‑asset) or several (multi‑asset) portfolio holdings from an existing fund that is nearing the end of its life or wants more time/capital to compound. Existing LPs in the selling fund are offered a choice to sell for cash at a negotiated price or roll into the new vehicle. A lead secondary buyer provides capital, and the transaction is typically vetted by the fund’s LPAC and supported by an independent fairness opinion or competitive process.

Great companies often need longer than a fund’s 10‑year term. Rather than selling early or starved of follow‑on, the GP re‑underwrites the asset(s) into a vehicle designed for a fresh 3–5‑year value‑creation plan—often with additional reserves for growth M&A, go‑to‑market, or working capital.

Day‑to‑day, this can look like a mix of deep diligence (you’re being re‑underwritten), incremental governance work (board confirmations, information‑rights hygiene), and sometimes new faces at the table (the secondary lead may take an observer seat). Most shares remain held by a fund entity, so company‑level consent/ROFR is seldom triggered—though any direct co‑invest or SPV positions may require company sign‑off under your charter.

The role of LP‑led secondaries

In an LP‑led secondary, a limited partner (pension, endowment, fund of funds, family office) sells its interest in a VC/PE fund to another institution. The buyer steps into the seller’s shoes, entitled to future distributions and obligated for any remaining capital calls. These trades clear at a discount or premium to NAV and are often bundled across multiple funds (“strip sales”). Sometimes the buyer also commits new capital to the GP’s next fund (“stapled primary”).

This is often motived by portfolio rebalancing (the “denominator effect”), liquidity needs, mandate changes, or admin simplification, usually nothing to do with your company. It’s a fund‑level liquidity market.

Founders usually feel relatively little impact from these transactions. LPs don’t sit on your board or negotiate company‑level terms; that’s the GP’s job. You might see incremental information requests as the GP updates data rooms for the fund sale, but your cap table and governance don’t change. If a stapled primary is involved, your GP may have more fresh capital across future funds, indirectly helpful for follow‑ons in later rounds.

Summary

Taken together, these markets form a three‑layer liquidity stack: (1) founder/employee‑level programs for personal diversification and retention, (2) GP‑level processes that reset the fund’s time horizon around your company, and (3) LP‑level trading that keeps capital sources healthy. Founders don’t control GP/LP‑level transactions, but you can shape the impact by insisting on clean information practices, tight governance, and unambiguous communication. Do that and each layer becomes a stabilizer on the path to compounding value.